Does the use of AI erode our cognitive abilities and reduce our capacity for critical thinking? Most likely, yes, but we are still waiting for the studies to really confirm it.

Our core cognitive abilities, such as attention, working memory and IQ, are shaped partly by genetics and partly by environmental influences. These environmental factors include cognitively demanding activities as well as deliberate, cognitive training.

The plasticity of these cognitive functions is evident, for example, in the impact of education: as my research group and others have shown, each additional year of schooling increases IQ by approximately two points1. Plasticity is also demonstrated through the positive effects of working memory training, which have been shown to not only improve capacity, but also to transfer to everyday mental activities like mathematical learning2-4.

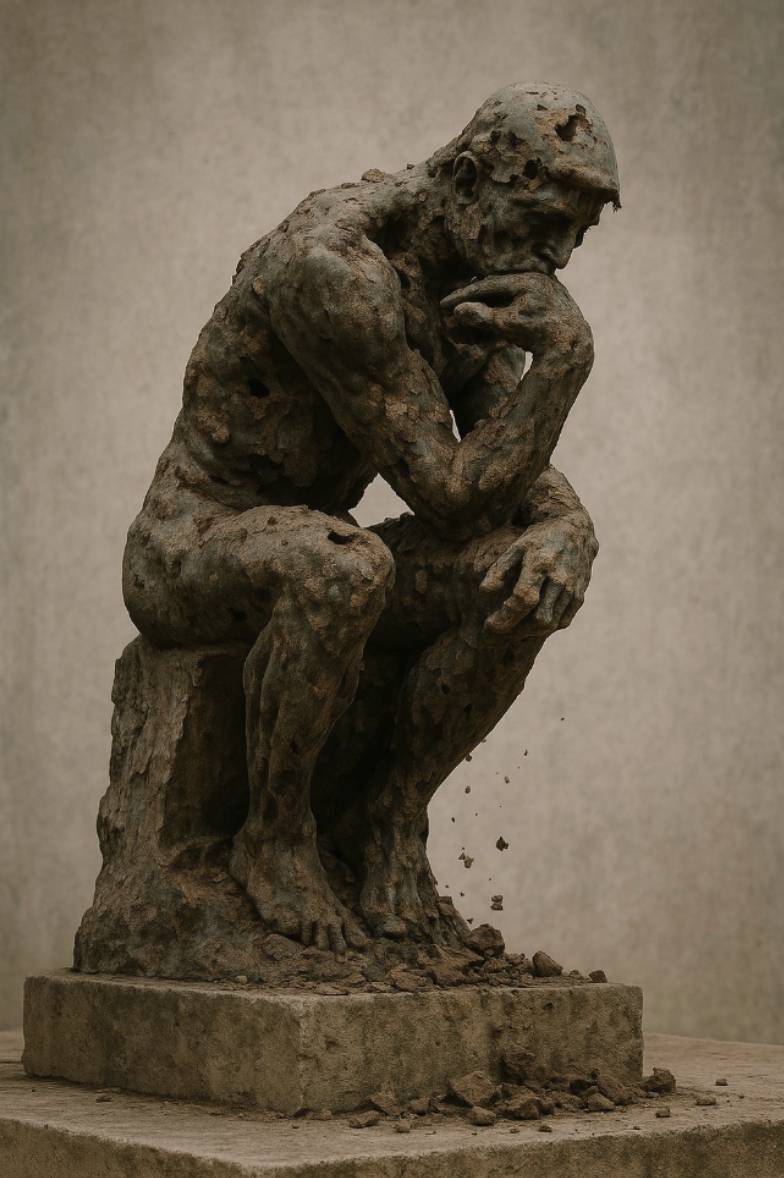

The flip side of this principle of plasticity is that lack of cognitive challenges has a negative effect on cognitive abilities. While the brain is not a muscle, both are biological organs that obey the laws of plasticity: lack of challenges lead to deterioration of function. That is why astronauts make time for physical training each day.

If we outsource cognitive effort to AI, the principle of plasticity suggests we may experience a decline in cognitive function. While AI can certainly be used to support learning5, it is more commonly used as a substitute for learning—reading texts for us, analyzing for us, writing the essay for us. A heartbreaking account of this phenomenon is described in the article ‘I am a highschooler. AI Is Demolishing My Education’6.

Critical thinking does not only require cognitive skills, but also factual knowledge and training in thinking logically. If we outsource the knowledge and thinking, it will likely impair our ability to think critically.

Some have suggested that the reversal of the Flynn effect7 might signal such an environmentally induced cognitive decline. While this trend predates widespread AI use, it may reflect other environmental influences, such as use of social media and lack of reading. A new study, however, attempts to examine the effect of AI directly, and it has received enormous attention online and in other journals.

In this study, published as a pre-print8, 54 participants were divided into three groups, each completing three essay-writing tasks: one group used ChatGPT (the “LLM group”), another used internet search, and a third wrote without any assistance (the “Brain group”). Brain activity was recorded using EEG during the tasks.

As expected, EEG analysis showed lower connectivity in the LLM group compared to the Brain group—after all, they were engaged in different activities. But the intriguing result came in the fourth round: here, the LLM group wrote an essay without assistance (LLM-to-Brain), while the Brain group now used an LLM. Surprisingly, EEG connectivity in the LLM-to-Brain group was lower than the original Brain group. This could suggest a lingering negative effect of prior LLM use.

However, there are major concerns about the study’s design. Crucially, there was no control group for the LLM-to-Brain condition. It’s entirely possible that writing a fourth essay was simply less engaging and included familiarization effect not controlled for. Without a proper comparison to a Brain-group also writing a fourth essay, firm conclusions are impossible. Moreover, only nine participants remained in the LLM-to-Brain group, which is too few for reliable group-level analysis.

Still, from the standpoint of neuroscience, we can reasonably expect that lack of cognitive engagement leads to functional decline. This is what the first principle of plasticity predicts. But the empirical data to confirm it in the context of AI use are not yet in.

2. Ericson J, Klingberg T. A dual-process model for cognitive training. NPJ Sci Learn. 2023;8(1):12.

6. Rosario A. I’m a High Schooler. AI Is Demolishing My Education. In. The Atlantic2025.

Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience